|

Home

Dossier

La

storia di Yukio, liberato dal braccio della morte grazie all'ostinata lotta

della madre

|

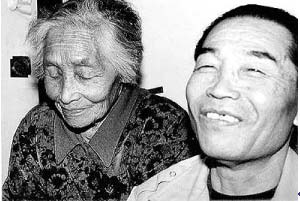

Hide Saito, 94, worked for years to gain the release of

her son, Yukio,

now 70, who was exonerated in 1984 after almost three decades on death row.

Japan's capital punishment system is cloaked in secrecy, largely ignored

by the public -- and sometimes dead wrong, according to the government's

own officials. |

On

death row in Japan, uncertainty by design

By

Doug Struck

- The Washington Post

TOKYO

-- For 34 years on death row, Sakae Menda dreaded the sounds. They always came

unannounced, a crude trumpet of death: the slide-click of metal as the small

window on his cell door was closed; its echo as a guard walked down the line of

cells, shutting each window in turn. Slide-click, slide-click, slide-click.

Another

cadence would then emerge, softly at first, a clap of the hard heels of guards'

boots, marching closer. It grew louder, until the sound carried the image

perfectly through the cell walls and his mind saw the line of grim-faced guards

file into the cellblock and stand at attention in the long corridor.

"Omukae!

Your time has come." The order was close, so close. In a cell next to

Menda, death was calling. In silent fear -- or, more rarely, with cries of

protest -- the prisoner was led to the gallows.

"When

that happened, my heart froze," said Menda, who escaped the call when the

courts acknowledged in 1983 that he had been imprisoned for a crime he didn't

commit.

As

America girds for the May 16 execution of Timothy McVeigh, attended by the blare

of publicity and clash of debate, Japan stands in contrast with a capital

punishment system that is cloaked in secrecy, largely ignored by the public --

and sometimes dead wrong, according to the government's own officials.

Japan

and the United States are the only industrialized democracies that still use the

death penalty, although it isn't uncommon in Asia. Japan's veiled and seemingly

arbitrary administration of the punishment has brought cries of outrage from

human rights groups and international bodies, including the United Nations.

For

50 men and four women on Japan's death row, the only warning they will receive

will be the appearance at their cell one morning of guards who will take them to

the execution chamber.

"It

was so frightening," said Yukio Saito, who was put on death row at age 24

and acquitted on reappeal in 1984 when he was 53. "Every day, I thought it

would be tomorrow. Every dawn, I thought it would be today."

For

some, the call never comes: The Justice Ministry has repeatedly passed over

certain prisoners until they are old and frail, in tacit admission that their

sentence may have been wrong. Nearly 20 inmates have been on death row for more

than a decade. At least 16 are over age 60; the eldest, 83, has been under a

death sentence since 1966.

The

Justice Ministry doesn't divulge the names of the inmates it selects for

execution and gives no explanation for the choice. Some are bypassed because of

pending appeals; 50 inmates who have been sentenced to death aren't "officially"

on death row yet because their initial appeal hasn't been heard. But even when

the legal efforts are done, inmates spend years or even decades not knowing

whether they are living their last day.

Human

rights groups have condemned this uncertainty. "It's inhumane. They go

through torture every day," said Sayoko Kikuchi, head of an abolitionist

group in Tokyo called Rescue!

Ironically,

many of those who have been on death row are ambivalent.

"I

think if I had known in advance when I would be executed, I would have gone mad,"

Saito said.

Japan

has executed 623 people since World War II, many of them in the chaotic

aftermath of the war. Now, Japan hangs but a few annually -- there were three

last year, five the year before. The numbers are minuscule compared with the 85

executions last year in the United States, which has roughly twice Japan's

population and 12 times as many murders.

To

learn about Japan's secretive death penalty system, the Washington Post talked

with some of the few men who were freed after being declared unjustly convicted,

as well as with prison guards, lawyers, relatives and others involved with the

death penalty process.

They

describe a system that is alien to most of the West. The death penalty is

carried out against the elderly (15 people executed since 1993 were over age

60), against inmates who show obvious signs of mental illness and against

prisoners still appealing their cases.

The

condemned sit for years in solitary confinement, under harsh prison rules.

Inmates are executed without the knowledge of their family members or lawyers --

to avoid, the government admits, emotional scenes, last-minute appeals or

demonstrations. The family is simply told later, "We parted with the inmate

today."

But

it also is a system that has a cultural logic to Japanese. The long wait for

execution is, in part, to allow the inmate time to prepare for death. The

seemingly arbitrary selection is made, again in part, according to which inmates

seem spiritually ready for their fate.

"In

a sense, to be given time, to do what you need to do to get over the fear of

death, is necessary," Menda said.

Now

76, he is a wry and bitter shell of the 23-year-old farm boy who was caught in

the wrong bed at the wrong time, framed by a prostitute and a policeman for a

double ax-murder in 1948.

"Over

the 34 years, I think I met about 80 inmates who were executed," he said in

an interview near his home in Kyushu in southern Japan. "The first time I

saw someone taken away, I became hysterical," he said. "I was so

scared. I cursed at the guards and threw things in my cell.

"I

was told by a priest: 'Menda-san, why don't you drop your appeal? For the sake

of your family, for your peace, why don't you accept your fate?'

"I

rejected that. But there is, in Japan, the concept of flowing water: You let go,

as the unseen power leads you," he said. "In the end, you get over the

wall of fear of death. When you finally get over that wall, it's like opening a

door."

Executions

are always carried out in the morning at one of seven "detention centers"

in Japan, each with a death row. The chosen inmate is brought from his cell

blindfolded. In the execution room, the noose is secured and the inmate's knees

are tied. "The idea is to have a clean death. They aren't supposed to

struggle and flop around," said Toshio Sakamoto, a prison officer for 27

years who is now retired.

At

most prisons, a separate room contains three to five buttons. On command, prison

officers each push one button. One -- the officers don't know which -- releases

a trapdoor that drops the condemned convict about 10 feet to his death. There

are no public witnesses. "I don't think any officers tell their family what

they do," Sakamoto said.

Opponents

argue that with so few executions, Japan should simply end capital punishment.

The United Nations considers the executions a violation of the International

Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which Japan has signed.

"The

death penalty has no legitimate place in the penal system of a modern, civilized

society," Gunnar Jansson, a representative of the Council of Europe, said

during a visit to Japan in February to urge an end to executions.

"The

majority of the Japanese people think it is unavoidable to apply the death

penalty in the most cruel crimes," said Yukio Kai, a counselor for the

Justice Ministry's criminal affairs bureau. Pressed, supporters of the death

penalty also say it is a deterrent to crime, though the claim is unproven in

Japan as elsewhere. The homicide rate here declined gradually from 1950 until

1988 and then leveled off, irrespective of the number of executions, which has

ranged from zero to 39 per year.

More

fundamentally, capital punishment is simply "not a social issue" in

Japan, or much of Asia, where China leads the world in executions, said former

justice minister Hideo Usui. "The Japanese people express a strong will for

it."

"The

public in Japan is very harsh," said Koichi Kikuta, a law professor at

Meiji University and a leading opponent of the death penalty. "We are a

homogenous society, living together. If there is something shameful, we want to

cut out that part from the rest of society."

|